E. Thomas & Williams - since 1860

E. Thomas & Williams - made in Wales

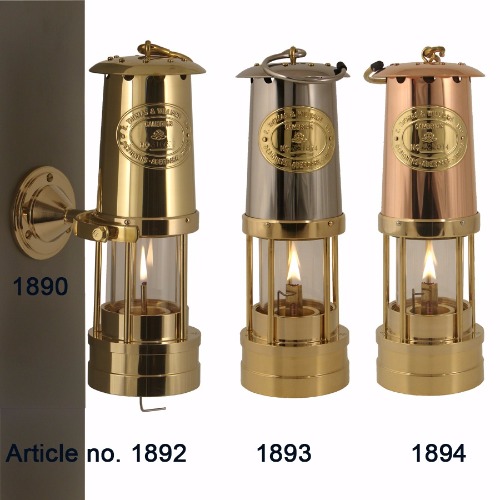

Height 260mm. Diameter 90mm. Weight 1.350g.

100ml oil container. Burning time 15-20 hours.

Flat burner using 12,5 mm wick

Spare glass

Spare wick

Other spare parts

The miner’s safety lamp

In the olden days the material of the bonnet (the hat) of a safety lamp reflected the owner’s rank in the mine:

Safety lamps with bonnets of steel (not stainless in those days) belonged to the miners. Those made of brass were meant for the foremen, and those of copper for the heads.

The safety lamp was constructed in a way to prevent the flame from igniting combustible gas. The quite unique air-intake inside the bonnet prevented the heavier explosive gasses from reaching the flame. The special device in the bonnet preventing the heavier explosive gasses from reaching the flame is not built into the lamps of today! With a small device in the lamp’s bottom, the height of the wick can be adjusted.

The history of the miner’s safety lamp

In the early days of mining candles made up of various fatty substances, animal as well as vegetable ones, were the main source of artificial light. The naked flames caused many explosions with subsequent casualties. In 1814 alone, more than 160 men in Great Britain died by mine explosions. 3 men’s contributions in the period of 1813-1817 meant a breakthrough for the safety in coal mines:

Dr. William Reid Clanny of Sunderland presented his candle-burning safety lamp to the Royal Society of Arts in London.

George Stephenson‘s oil-burning safety lamp was presented to the Literary and Philosophical Institute of Newcastle-upon-Tyne.

Sir Humphrey Davy’s oil-burning safety lamp was presented to the commissioners of the Society of Arts.

Actually, George Stephenson’s “Geordie” and Sir Humphrey Davy’s “Davy” were developed more or less in parallel. However, mine explosions continued, and as late as in 1884 that lead the British Government to appoint a Royal Commission to find the cause of the accidents; the tests were to be conducted at Woolwich Arsenal by a specially selected committee including several members of the Royal Commission.

They received more than 250 lamps from makers, inventors and users in Germany, Belgium, France and the UK, very much encouraged by an award of 500 pounds sterling for the best safety lamp. Before any conclusions were made, M. J. B. Marsuat, a French mining engineer, proved to the committee that the test principle was entirely wrong. The commissioners were not considering the importance of the airflow variations in the coal mines and their impact on the functions of the safety lamps. This was noted by the committee. And that was really the second breakthrough for the safety in coal mines. For it explained most of the “inexplicable explosions” through the past.

The conclusion of the committee was then somewhat modified. No lamp then in use was entirely fulfilling the set requirements. The prize of 500 pounds sterling was never awarded. In 1886 the Royal Commissioners, however, finally decided in favor of four lamps, “in which the quality of safety, to a pre-eminent degree, is combined with a simplicity of construction, and with an illuminating power at least fully equal to that of the lamps hitherto in general use. These four lamps were: Gray’s Lamp, Evan Thomas No. 7, Marsuat and Meuseler Bonneted. In our experiments the No. 7 has given, upon the whole, the best results”.

All European safety Miner’s lamps derive from the principles of the original 3 English Miner’s lamps “Clanny”, “Geordie” and “Davy”. As a curiosity the “Scotch Davy” lamp was found to be the worst working safety lamp - violating the physical laws - and the use of this lamp was disapproved by the commission.

Ref. links:

www.mininginstitute.org.uk

www.msha.gov/programs/hsapubs/2001/jan01.pdf